Diabetic Kidney Disease 1980 to 2025: A Personal Reflection

There is now, in 2025, widespread appreciation across the UK Kidney Association that diabetes is the commonest cause of kidney disease and that managing this disorder is a key priority for our community. However, that was not always the case. Although my experience doesn’t stretch back 75 years, I have had a 40-year experience and have had the privilege of seeing first-hand the enormous changes that have occurred in relation to the approach to diabetic kidney disease over this time. From the 1980s to the present, substantial advances have been made in the management of diabetic kidney disease, leading to a significantly improved outlook for individuals with this disorder.

1980: A Gloomy Outlook

I recall very clearly lectures I gave in the early 90s in which I described the prognosis in relation to diabetic kidney disease. The key message was that once a person with diabetes developed significant proteinuria they were destined to either die or reach end-stage kidney failure within 5 to 7 years and indeed we saw many people progress even more rapidly. The number of people with diabetes who went onto dialysis was small compared to the number of people affected because of the huge attrition related to cardiovascular disease and indeed before the 1980s many individuals with diabetes and end-stage kidney failure were not even offered end stage kidney failure treatment options.

It had been a British Nephrologist, Professor Clifford Wilson working in Harvard in collaboration with pathologist Paul Kimmelstiel whose work formed the anatomical basis for understanding diabetic kidney disease as a clinical entity.

Also in the United Kingdom the work of a UK endocrinologist Professor Harry Keen at Guys Hospital had been pivotal in identifying albuminuria as a marker of kidney disease in diabetes. Professor Keen contributed to the St. Vincent Declaration (1989), setting international benchmarks for prevention of diabetes complications.

It is interesting to reflect on the fact that most of the patients with diabetes who reached end-stage kidney failure in the 1980s had type I diabetes. The phenotype of the people with type 2 diabetes was very much as it used to be described as “maturity onset” and people generally presented in their 60s and 70s such that very few of them survived through to end-stage kidney failure. The change in phenotype of people with diabetic kidney disease to those with type 2 diabetes has been perhaps the most extraordinary element of the history of diabetic kidney disease.

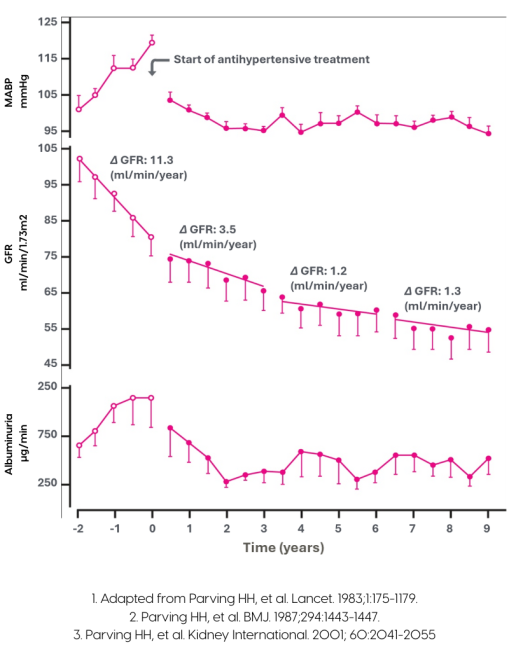

The first glimmer of hope on management came from continental Europe with the seminal paper published by Hans Parving in 1983 demonstrating the powerful beneficial effect of blood pressure control in prevention of progression of diabetic kidney disease.

It may surprise readers to know that the blood pressure agents used in this study that had such a beneficial effect were beta-blockers and thiazides.

1990s and 2000s: Emerging Therapies and Insights

I undertook my research at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston (where the first kidney transplant had been undertaken) and at the time I chose to work in the Immunogenetics lab of Bernie Carpenter. Down the corridor was the nephrology department led by Prof Barry Brenner and this department was incredibly active with a number of prominent fellows who went on to become leaders of US and indeed worldwide nephrology. Barry Brenner’s work which he undertook together with Thomas Hostetter and Sharon Anderson among others focused on micropuncture studies of rat tubules to study glomerular capillary pressure and in their seminal work they demonstrated the beneficial effects of reducing trans glomerular capillary pressure with enalapril in rat models of CKD.

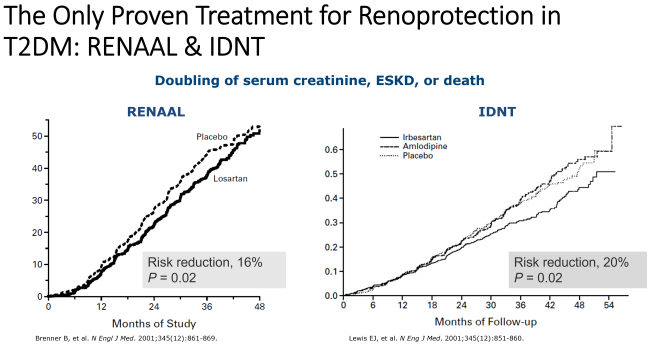

Over the 1990s this discovery was rapidly translated into clinical practice with a multitude of studies looking at both ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on progression of CKD and the identification of the benefits of these drugs over and above their blood pressure lowering effects in people with diabetic (and indeed also non-diabetic) kidney disease.

UK nephrology did not appear as interested in this disorder but there were notable exceptions. The team at Cardiff which included Professors Aled Phillips, Donald Fraser and Tim Bowen undertook both clinical and laboratory-based work to better understand and recognise early diabetic kidney disease. It was also one of our former presidents Prof Peter Mathieson who supported research to better understand the cellular basis of albuminuria.

2000s: The train slows down and the problem grows

By 2001 we were clear on what needed to be done and indeed Nephrologist were actively getting their patients onto ACE inhibitors or angiotensin 2 inhibitors but the vast majority of people with diabetes and kidney disease were sitting in either primary care or other clinics. Therefore, implementation of this effective treatment was very slow and did not reach a significant proportion of the patients that it was intended for.

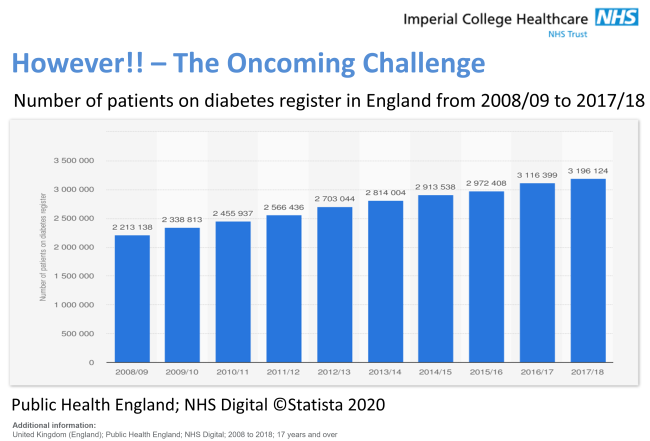

Furthermore, over the 1990s and the 2000’s there was an extraordinary increase the number of people with diabetes driven predominantly by obesity and type 2 diabetes. This was a worldwide phenomena and led to a significant growth in the number of people with diabetes on end-stage kidney failure programs.

2010s to Present: Targeted Therapies and Optimising Outcomes

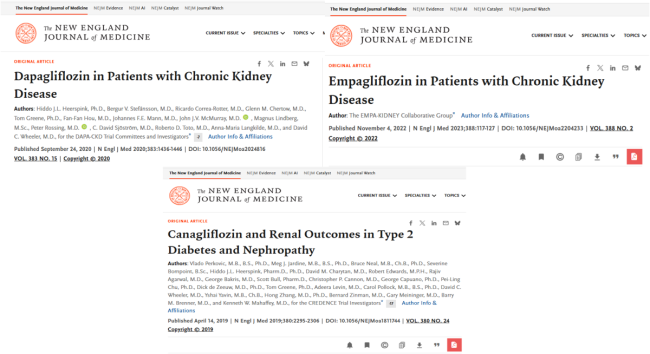

In 1835 it was identified that a substance from the apple tree bark known as phlorizin resulted in glucosuria. It was in the 1980s that scientists discovered that there were glucose transporters in the proximal tubular of the kidneys (Sodium Glucose Co-Transporters) and the agent from apple bark tree blocked this transport. The development of pharmacological interventions that utilised this discovery took a while but in the early 2000’s selective SGLT2i were being trialled. They were introduced as a treatment for diabetes and as part of the standard requirements for FDA and European approval the Pharma companies undertook cardiovascular outcome trials with all the new SGLT2is including dapagliflozin, canagliflozin and empagliflozin. The results of these trials were extraordinary in that not only was the cardiovascular benefit identified but in every single SGLT2i trial there was significant benefit in relation to reduction in progression of kidney disease.

What followed was a truly remarkable period for nephrology and for people with diabetic kidney disease and at last time for British nephrology to get into the act. Subsequent kidney specific studies were undertaken with all of these agents and with significant involvement from British nephrologists including David Wheeler leading on the DAPA CKD and CREDENCE studies and Will Herrington and the Oxford Trials Unit leading on the EMPA kidney study. All the studies confirmed the significant beneficial effect of these agents.

Over this time there was also a significant increase in collaboration between the kidney and the diabetes community with the formation of the joint ABCD and Renal Association diabetes kidney guideline group. This group produced a plethora of guidelines to help clinicians manage people diabetes and kidney disease including guidelines relating to glycaemic control, blood pressure and lipid control in people diabetes. The guideline group was led by both a nephrologist and a dermatologist and the Renal Association lead has been Prof Indranil Dasgupta although he has recently passed the chain of command to Dr Rosa Montero. Subsequently the diabetes renal collaborative supported the production of the first international guidelines on the management of diabetes in people on dialysis. This collaborative approach to the management of diabetic kidney disease has been further advanced with close and indeed formal relationships between the UK Kidney Association and many other organisations involved in the care of people with diabetes and kidney disease including the Primary Care Diabetes and Obesity Society, the Primary Care Cardiovascular Society and the British and Irish Hypertension Society. These collaborations indicate a real enthusiasm and determination to improve the care of people with much earlier diabetic kidney disease then we see in secondary care

Just like buses as the beneficial effects of SGLT2i were being rolled out nationally further pharmacological interventions were found to have significant beneficial effects on preventing progression of diabetic kidney disease including the novel mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone and the GLP1 receptor agonist semaglutide.

Compared to the 1980s we now had a range of treatments that could effectively manage people with diabetic kidney disease significantly slowing down progression, reducing cardiovascular events and potentially pushing the need for end-stage kidney failure treatment beyond the lifespan of many of the individuals affected by diabetic kidney disease. The gloomy 1980s has now been replaced with the optimistic 2020s with huge enthusiasm for shifting the dial from managing advanced kidney disease to optimising people with early diabetic kidney disease and thereby make huge impact on their long-term health and quality-of-life. Everything is now possible!

Dr Andrew Frankel

Consultant Physician and Nephrologist

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust